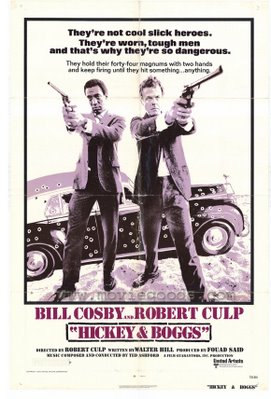

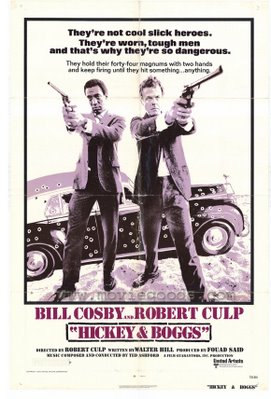

“They’re not cool slick heroes. They’re worn, tough men and that’s why they’re so dangerous. They hold their forty-four magnums with two hands and keep firing until they hit something…anything.”

That’s the very lengthy tagline from the original movie poster, and it only begins to hint at the awkwardness of Robert Culp’s directorial debut. Rarely are so many elements of a feature film so impressively awful: I’ll allow that Bill Butler’s cinematography is done no favors by the DVD transfer, which makes everything look like it was shot through a dirty windshield, but the unimaginative framing can’t be fully blamed on pan-and-scan. Butler would shoot

Jaws a few years later, and editor David Berlatsky went on to cut

The Deep; maybe the plodding “style” they achieve here convinced producers that they’d have a feel for underwater movement.

This is not a

good movie, but it is an interesting one, if only for the particular position it occupies in detective-movie history, clumsily introducing concepts that soon would be improved upon before finally being reduced to lazy tropes. The .44 magnums and football stadium showdown put

Hickey and Boggs in the lineage of

Dirty Harry, but it's the way the movie anticipates neo-noir that's most remarkable.

Hickey and Boggs was released in 1972, before

The Long Goodbye (73),

Chinatown (74), and

Night Moves (75) made the impotent private eye such a sign of the times; to

Long Goodbye it bequeaths a vengeful ending, to

Chinatown an embarrassingly injured protagonist, to

Night Moves a hero emasculated by his sexually determined wife—in one of the film’s most outrageous scenes, Robert Culp’s Boggs goes to watch his ex-wife in a strip club. “Eat your heart out,” she spits at him. Additional tethers: The slimy (and improbably named) Lester Fletcher even has the effete manner and soulless gaze of Henry Gibson’s quack in

The Long Goodbye; the lieutenant crossing paths with Hickey and Boggs is played by James Woods, who would soon turn up as the murderous motorcyclist in

Night Moves. And picking up tradition from

The Killers and

Point Blank, Hickey and Boggs re-introduces what the

San Francisco Chronicle’s Dennis Harvey calls “the great buzzed-at-high-noon portraits of L.A. as a town of the disappointed and the casually depraved, each mere miles away from the gated winner’s circle.”

Bill Hickman, who drove cars in

Bullit and the

French Connection, even gets a helicopter at his disposal here but with no thrilling results. Vincent Gardenia and Michael Moriarty, who’d be so good together in

Bang the Drum Slowly, are useless. And Rosalind Cash escaped one barren LA (

The Omega Man) to wind up here, trapped under rubble? Syl Words (one of the spaghetti-breakfasters in

A Woman Under the Influence) has the most memorable line in the film. When someone dismisses a woman as a “desperate, nasty bitch,” Words’ black militant Mr. Leroy warns: “Desperate, nasty bitches are dangerous, brother.”

Is it worth noting here that the money to produce

Hickey and Boggs came from Culp and Cosby’s old

I Spy cinematographer, who had in the interim made his fortune with the invention of the

cinemobile?